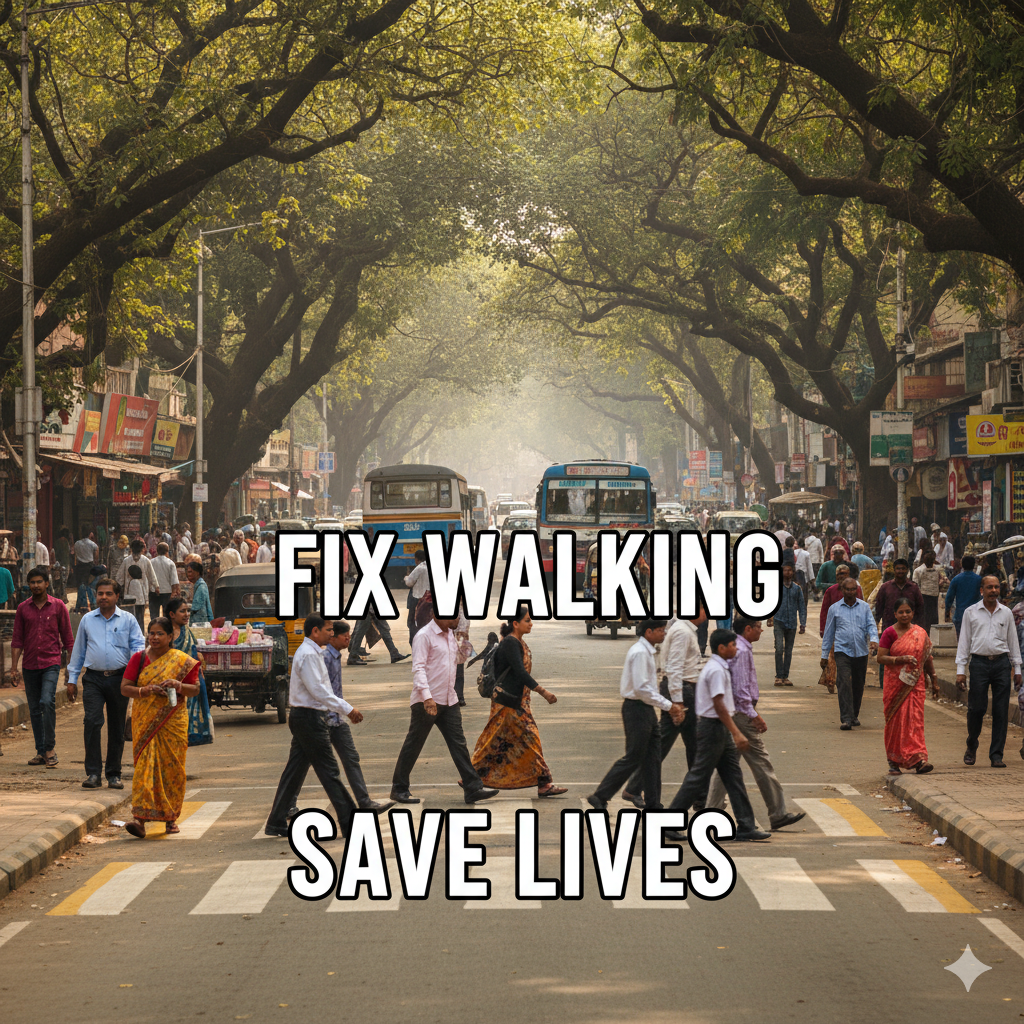

India’s cities are built around vehicles, not people. Yet the central policy framework already says the opposite: the National Urban Transport Policy (2014) urges cities to “move people, not vehicles” & prioritise walking/cycling infrastructure

Big picture: India’s cities are built around vehicles, not people. Yet the central policy framework already says the opposite: the National Urban Transport Policy (2014) urges cities to “move people, not vehicles” & prioritise walking/cycling infrastructure. Standards like IRC:103-2012 spell out footpath design & safety, but implementation is uneven.

Why walkability matters (evidence):

- Safety: India recorded 1,68,491 road deaths in 2022; pedestrians are roughly ~19–20% of fatalities—tens of thousands of lives each year. Making streets safe for walking is a direct public-health intervention.

- Health & climate: Walkable streets cut car trips (air pollution, emissions) & boost physical activity. Chennai built 100+ km of quality footpaths (2013–2019); studies found 9–29% of people walking on improved corridors would otherwise have used private motorised modes—tangible mode shift.

- Economic productivity: Proximity & reliable walking access shrink commute times, widen labour catchments for firms, lift local retail spend, & reduce congestion externalities—core aims echoed in MoHUA programmes.

What’s already happening (policy & pilots):

- MoHUA’s “Streets for People” Challenge (under Smart Cities Mission) helps cities convert quick pilots into permanent, people-first streets; companion efforts document 50+ flagship projects & show how placemaking improves safety & commerce.

- Momentum since 2020: Across 33 cities, India has delivered 350+ km of improved footpaths, 220+ km of cycle tracks; 15 cities adopted Healthy Streets Policies; 1,400+ km of streets are under revamp plans.

Design building blocks (decoded):

- Continuous, obstruction-free footpaths (frontage/utility/pedestrian zones), minimum widths & kerb ramps per IRC:103-2012; at-grade crossings with refuge islands; speed management (raised tables, tighter curb radii); universal accessibility; shade & heat-resilient materials.

Risks & watch-outs:

- Paper compliance vs on-ground quality: Narrow, blocked, or discontinuous footpaths; missing crossings; signal timings biased to cars.

- Institutional friction: Multiple agencies (roads, utilities, traffic police) slow delivery; O&M budgets & enforcement often weak.

- Equity & inclusion: Designs must serve seniors, children, persons with disabilities—explicitly required by NUTP—but frequently overlooked.

Signals of demand & change:

- WHO’s 2023 report re-emphasises the global push to protect vulnerable road users; Indian cities are piloting pedestrianisations (e.g., heritage cores), riverside walks & connectors; advocacy pushes (e.g., Bengaluru pedestrian/cycle tunnel proposal in an IT corridor) show growing public appetite for safe, direct walking links.

Bottom line: Safer, cooler, more productive Indian cities require continuous, standards-compliant walking networks—linked to transit, jobs & services—scaled from pilots to city-wide programmes with stable funding, maintenance, & enforcement.