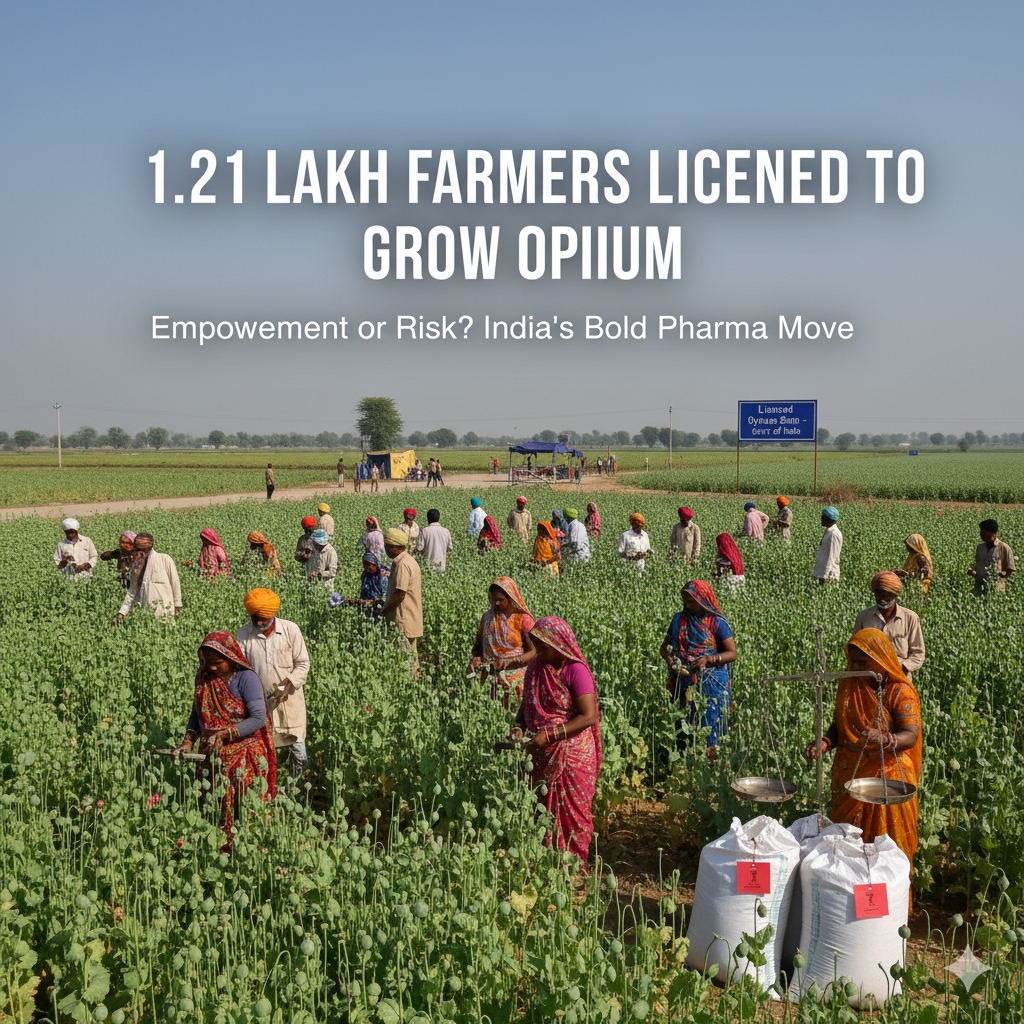

India’s government licenses 1.21 lakh farmers in MP, UP & Rajasthan to cultivate opium. A major policy shift for pharma supply and rural income — but raises questions of control and misuse.

In a move that has stirred debate across agriculture, pharma, and policy circles, the Government of India has granted official licenses to 1.21 lakh farmers from Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh to legally cultivate opium (afeem) for the 2025–26 agricultural season.

The decision, while not entirely unprecedented, marks India’s biggest legal expansion of opium cultivation in decades, signaling a renewed focus on pharmaceutical production, export potential, and rural income generation — but also reigniting concerns over diversion, misuse, and regulatory control.

India is one of the few countries in the world legally permitted to cultivate opium poppy (Papaver somniferum) under strict government supervision.

This year, the Central Narcotics Bureau (CNB) and the Department of Revenue (Finance Ministry) have expanded licensing to over 1.21 lakh registered farmers spread across three states:

Each farmer is allotted a specific landholding size (typically 5–10 ares) for cultivating the poppy plant, whose latex yields raw opium, a critical base for pain-relief medicines and opioid derivatives like morphine, codeine, and thebaine.

The expansion is part of a strategic reform in India’s narcotics and pharma policy.

The goal: to boost domestic production of medical opioids, reduce dependence on imports, and tap into a global pharmaceutical market that’s tightening due to supply shocks and synthetic opioid restrictions.

India already holds a long-standing status as a UN-recognized legal opium producer, alongside Turkey and Australia. However, its output has remained limited for decades due to outdated cultivation methods and restrictive licensing.

By expanding the farmer base and upgrading processing standards, the government aims to:

All cultivation is conducted under the direct control of the Central Bureau of Narcotics (CBN).

Farmers receive government-issued licenses specifying:

The latex extracted from the poppy capsules — containing morphine, codeine, and related alkaloids — is collected, weighed, and sealed by government officials on-site.

The raw material is then sent to Government Opium and Alkaloid Factories (GOAFs) in Neemuch (MP) and Ghazipur (UP) for processing into pharmaceutical-grade derivatives.

A licensed opium farmer can earn significantly more than from conventional crops like wheat or mustard.

Depending on yield and purity, per-acre earnings range from ₹1.5 lakh to ₹3 lakh annually, with potential bonuses for higher alkaloid content.

For small and marginal farmers, this represents a lucrative income source, especially in drought-prone areas of Malwa and Mewar, where rainfall volatility makes traditional farming risky.

Moreover, India’s legal opium exports bring in foreign exchange revenues, particularly from pharmaceutical-grade morphine and codeine formulations supplied to Europe and Japan.

Despite its legal framework, opium cultivation has long carried a shadow of controversy.

Concerns revolve around:

To mitigate this, the government has rolled out digital monitoring, drone surveillance, and GPS fencing across licensed zones. Farmers found guilty of diversion risk license cancellation, arrest, and permanent disqualification.

The government is also experimenting with concentrated poppy straw (CPS) technology, already in use in Australia and Turkey, where morphine-rich capsules are harvested mechanically instead of manually lancing the poppy pod.

If successful, this would:

The pilot CPS projects in MP’s Mandsaur and Rajasthan’s Chittorgarh are expected to scale nationwide by 2026.

While the move empowers rural farmers and strengthens India’s pharmaceutical independence, critics argue it could also test India’s enforcement capacity.

If oversight fails, illegal diversion could undermine not only domestic control but also international trust in India’s legal opium program.

The government’s challenge lies in balancing profitability with precision control — allowing farmers to thrive while keeping the narcotic economy transparent and accountable.

India’s decision to license 1.21 lakh opium farmers is both bold and risky — a policy that walks the fine line between empowering agriculture and containing narcotics misuse.

If managed correctly, it could turn rural belts in MP, UP, and Rajasthan into global suppliers of legal medical opioids, boosting exports and rural income.

If mismanaged, it risks reviving old problems of illegal trade and addiction.

Either way, the move marks the beginning of a new chapter in India’s controlled narcotics economy — one that could redefine how the world views afeem not as contraband, but as a regulated cash crop with a medical purpose.